From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Thank You For Smoking

Originally published 3/25/06

Full review behind the jump

Full Disclosure: The producers of Thank You For Smoking, David O. Sacks and his company Room 9 Entertainment, are the same people who purchased my screenplay Queen Lara, which they intend to make their next feature. And so I’m personally well-acquainted with them and even spent a day on the set of this film. One could suggest without being wildly-paranoid that I have an indirect financial interest in this movie’s success. I like to fancy that none of this affects my ability to objectively critique the film (I would not be so egotistical as to presume an endorsement from me will make a flyspeck’s difference to the box office), but I’d prefer to err on the side of over-divulging when it comes to any potential for bias.

Thank You For Smoking

Director: Jason Reitman

Writer: Jason Reitman, based on the novel by Christopher Buckley

Producer: David O. Sacks

Stars: Aaron Eckhart, Cameron Bright, William H. Macy, J.K. Simmons, Katie Holmes, Sam Elliot, Rob Lowe, Adam Brody, Robert Duvall, Maria Bello, David Koechner, Kim Dickens

It was the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan who said "Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but they are not entitled to their own facts." And it seems that in this age in America, facts are not so much revered as considered a grave annoyance to certain entrenched interests. From professional global warming “skeptics” bankrolled by ExxonMobil to “Swift Boat Veterans” who didn’t actually serve on Swift Boats to the campaign by religious extremists to cram “intelligent design” into the gap between the scientific and colloquial understandings of the word “theory”; in today’s cacophony of information, it’s often inconvenient to adjust to reality when, for much less money and effort, you can simply hire a lobbyist to deny that reality.

Thank You For Smoking, adapted by Jason Reitman from the satirical novel by Christopher Buckley, is not specifically about cigarettes, they simply provide the playing field. This is a movie that assumes, optimistically, that its audience already knows that a) cigarettes are addictive, b) they will kill you, and c) cigarette companies would prefer that points a and b not be emphasized. This clears the way to the true subject matter: lobbyists, the handsomely-compensated sophists who, squid-like, spray clouds of rhetorical ink in the face of irritating facts. It’s a profession that, as Nick Naylor (Aaron Eckhart) explains to his son Joey (Cameron Bright), requires “a moral flexibility most people don’t have.” Say that line to yourself, see how it linguistically casts a catastrophic personality failing as a rare strength, and you understand how Nick Naylor operates. Thanks to Reitman’s witty script and Eckhart’s perfectly-pitched performance, watching him operate is a whole lot of fun.

Comedy is the genre for people who never learn their lesson, from The Merry Wives of Windsor on up to Frasier. And, since he isn’t in our world where he can do real harm, we’re happy to have Nick Naylor be exactly who he is, since it’s not in his design to enjoy life as anything else. Glib, supremely confident, and with a “For Sale” sign proudly dangling from his moral compass, Naylor is the most gab-gifted spinmeister going. And he needs to be in order to advocate for a product that kills over 1,000 people a day.

This is about as much as the movie has to hang its hat on. Few of the conflicts which bubble up have enough staying power to be considered a plot; it’s more of a breezy tour through the world Naylor occupies, carried by his undeniable charms and a wicked sense for unsparing mockery.

He sits for regular lunches with “The MOD Squad” (it stands for Merchants of Death), lobbyists (Maria Bello and David Koechner) for similarly galling but statistically less-lethal products. He tries to incorporate the proper rearing and education of his son into his lifestyle with surprising results. He makes a pilgrimage to the offices of Hollywood superagent Jeff Megall (a very funny Rob Lowe) in order to make smoking cool in the movies again. He drops in on “the original Marlboro Man” (Sam Elliott), who now has cancer and is angry about it. An aggrieved domestic terrorist makes a threat on his life. And an ambitious reporter for the deliciously-named “Washington Probe” (Katie Holmes), prepares a profile on Naylor while dropping salacious hints about wanting to know “where the devil sleeps”.

The pleasure lies not in what Naylor is doing but how he navigates each of these challenges using only his gift for teasing human nature into spider webs of satisfying argument. It’s a superb showcase role for Eckhart, who in his sunny way gets to be as frighteningly persuasive as Michael Douglas was when he argued “Greed is Good” in Wall Street. It’s also one of the movie’s lost opportunities – his ability to turn the tables of any debate is so uncanny that you rarely concern yourself with how he’s going to triumph. William H. Macy does yeoman’s work as a fussy and moralistic Senator who wants to put a skull and crossbones on all cigarette packs, but the movie never kids you that he’ll prove a worthy adversary even as the two head for a showdown.

It’s worth spending more time on the cast, which is generous with talent for such a low-budget film. Most co-stars rarely surface for more than a scene or two, and Reitman matches their abilities to broad character types in order to milk the most laughs out of their time. Robert Duvall deftly skewers the racist Old Southern gentry as julep-loving tobacco kingpin “The Captain”, and J.K. Simmons barks his way through the role of Naylor’s boss at the “Academy of Tobacco Studies”, bringing some of his patented staccato bursts of hot air over from the Spiderman franchise. Even Adam Brody of T.V.’s The O.C. gets a few minutes to shine as Jeff Megall’s enthusiastically vapid go-getter assistant. It takes exposure to workings of the movie industry to appreciate how truly merciless the Hollywood section’s lampooning is, but it should provide laughs even to the uninitiated.

For all the timeliness of its satire, Thank You For Smoking is not likely to emotionally engage, it covers too much ground and skips too briskly along the way for that. As a feature filmmaker Reitman has a rookie’s enthusiasm and willingness to commit to off-the-wall ideas. That has its ups and downs. But his most fruitful decision is to trust our ability to embrace Nick Naylor as the picture’s nominal hero. If the tobacco industry’s slippery secret weapon is the invulnerable exhortation that people can make up their own minds in a free society, it’s this movie’s most winning gesture – we get to know Nick Naylor in all his cynical glory, and we’re happy to share in his adventures for an hour and a half. As a society he’s bad for us, but you can’t deny that he appeals to a certain part of your brain.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

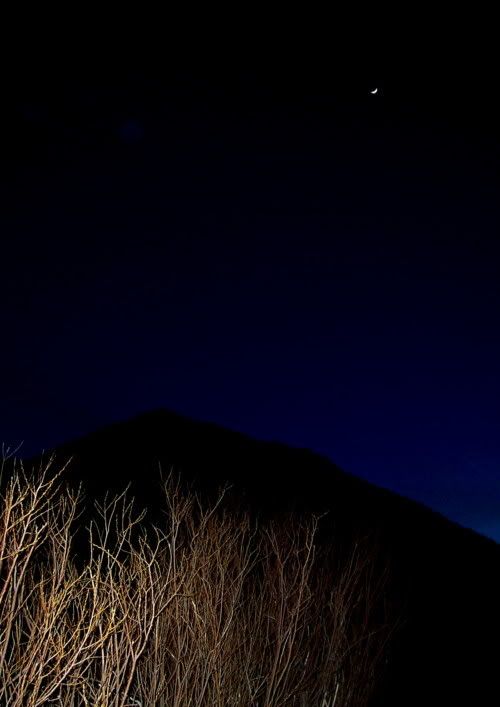

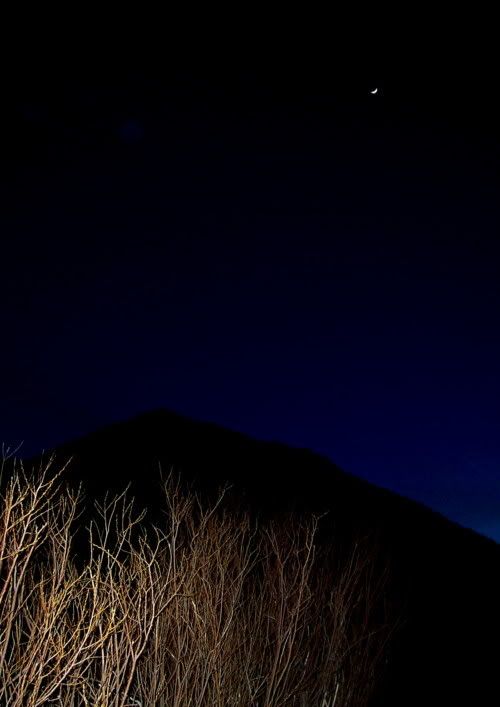

Bedrock, Colorado

Image Copyright 2007 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Ultraviolet

Originally published 3/9/06

Full review behind the jump

Ultraviolet

Director: Kurt Wimmer

Writer: Kurt Wimmer

Producers: John Baldecchi, Lucas Foster

Stars: Milla Jovovich, Cameron Bright, Nick Chinlund, William Fichtner, Sebastien Andrieu

What compels us about superheroes are not their strengths but their weaknesses. We sat down when we saw Superman fly, when the Kryptonite showed up we decided to stay in our seats. In Ultraviolet we have a heroine who is in all ways I can divine completely invulnerable, who can outfight any army unaided, reinvent the law of gravity, and manipulate space and time in ways previously accessible only to Greek Gods and high-level Scientologists.

She’s some sort of vampire, I gather from the teeth and all the talk of blood. In her futuristic world, a genetically-engineered version of the old vampire plague, designed to create supersoldiers, has instead created a feared subclass of citizenry – the Hemophages. They are extremely contagious, and the world lives in desperate fear of infection, turning both legal and spiritual authority over to a fascistic elite medical clique that promises to keep them safe. Violet (Milla Jovovich) is a Hemophage, which is what gives her many of her powers. Other powers come from head-spinning machinery like portable holes into an alternate dimension that allow her to store dozens of guns and a full-length sword up her sleeve, and a belt buckle that contains what appears to be a miniature black hole/supernova that lets her walk on the ceiling and ride her motorcycle along the side of a building. This equipment did not come from Q Branch.

But she insists she does have a weakness. She’s “dying”, so she says, from her infection. But since she’s had it for 12 years and is still vigorous enough, and all the infected we see are superstrong, superfast and devastatingly pretty, and need only the occasional ingestion of fresh blood to keep going, we could all stand to be “dying” like that. Really, Violet is no more dying than anyone who wears black and writes bad poetry. And so to my point above – we have here a movie which rarely bothers to make sense, cares for nothing but action and features a character who will never be in danger.

The story begins as Violet infiltrates a laboratory posing as a courier to pick up a package – one wonders about the prospects of the FedEx Company surviving the invention of the portable dimension hole. To get the package she must pass an absurdly invasive screening procedure where she’s X-Rayed, has blood drained out of her wrists and needles poked into her eyes, her voice is analyzed, and she must walk naked down a long hallway with mood lighting. The MPAA continues its determined work molding the fetishes of the coming generation by deciding that a bare backside is acceptable PG-13 fare and tickets to its viewing may be sold to all, while the female breast is evil, harmful and forbidden without a parent or guardian around. So it is safely hidden away in this picture, as is any blood from the hundreds of people violently murdered by blade or bullet.

This entry procedure, which takes up several warehouse-sized rooms and about a billion dollars’ worth of equipment (pity the pizza delivery boy), is so thorough that it absolutely, positively could not be fooled. Except that it is.

The package is rumored to contain a weapon that will wipe out the Hemophages once and for all, so she and her underground cell want it. What it actually contains, and how it affects the Fate of All Mankind, sets Violet against both the human world and her vampire brethren, and she’s catapulted into what is little more than 85 minutes of chasing, fighting, more chasing, more fighting, brief soul-searching, more chasing, more fighting, confusing exposition, more chasing, and so forth. Eventually you’ll learn why the chasing is happening – what you won’t learn is why Evil Mastermind Daxus (Nick Chinlund) would finally have the key to all his ambitions and the first thing he does with it is stick it in the mail.

Better to just try and enjoy the fighting if you can. In one scene Violet fights dozens of Asian Men in Suits. They were described as being neither human nor vampire, I believe the movie called them “Blood Chinois”, which sounds terribly important and interesting, except that in seconds they are all dead. So all I learned from that encounter is that Blood Chinois = Asian Men in Suits.

Another clash happens between two swordsmiths in a completely darkened room – their weapons have somehow caught on fire and provide the only illumination. It looks like an angry luau, I remember thinking. Many of Violet’s feats against superior numbers become repetitive; her foes insist on enclosing her in a perfect circle, then falling as one from her blows like the stormtrooper version of Ring Around the Rosie.

I’m kind of skipping around. I plead coercion – the movie is forcing this on me. The wall-to-wall digital effects are watery and blurred, the fight choreography busy without having any sense of pace or build, and the dialogue is adolescent flapdoodle. A Purple Heart to the actor who must try and convincingly snarl “Now it’s on!”. There is one design flourish I like – in the future you can print out disposable phones on a strip of paper from a vending machine. And the opening credits are laid out in lurid comic book style, each name emblazoned on a phony issue of Violet’s fantastic adventures, while subtlety-pummeling composer Klaus Badelt does his best impersonation of Danny Elfman’s Spiderman score.

The choice is imaginative, but I’m not sure if we’re meant to think that Violet is actually a comic book character, or if they’re just arguing that she should become one. There’s a lot I’m not sure of about this movie. That it stands feeble in comparison to other movies of its type, though, that I’m secure about.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Campground near Twin Lakes, California

Image Copyright 2005 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Block Party

Originally published 3/6/06

Full review behind the jump

Block Party

Director: Michel Gondry

Writer: Dave Chappelle

Producers: Dave Chappelle, Bob Yari, Julie Fong, Michel Gondry

Featuring: Dave Chappelle, Mos Def, Kanye West, The Fugees, Erykah Badu, Common, Dead Prez, Jill Scott, The Roots, Big Daddy Kane, and many others

Dave Chappelle, former mid-level comedian, actor and writer turned multi-millionaire Comedy Central hitmaker, watches from the rooftops in Block Party – looks down on a bumping, electric rap concert that’s taken over a corner of Bed-Stuy. It only exists because he willed it so, and he could only will it so because he’s the multi-millionaire now. He’s digging the music, loving the chance to hang out with musicians he respects and admires, and absorbing the beneficent feelings of having given such a great entertainment to people who ordinarily wouldn’t be able to afford it.

But for all of that, he’s still up there, on the rooftop, not down on the street moving in the crowd. When he invites a member of the audience on stage to have a mock rap battle, and the guy playfully wrestles with him, Dave jokingly threatens to call security: “I’m worth too much money now!” It’s one of a tiny handful of moments where he reveals pained self-awareness covered by self-effacing humor. Dave Chappelle became the Fifty Million Dollar Man practically overnight, the mammoth renewal deal for his sketch comedy show obliterating any remaining chance of an anonymous life.

And in the wake of that he made a stunning gesture – pulling the plug on the show at the height of the mania around it. Now, in this combination documentary/concert film by long-time music video director and Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind filmmaker Michel Gondry, we see that in those first weeks of struggling with the change in his life he made another large gesture: putting on this show. It might have been a choice between this or a nervous breakdown. Or maybe he had both and only filmed this part.

The film covers the few days leading up to and including a concert Chappelle produced and hosted in Brooklyn in September of 2004, which featured a legends line-up of rap and hip-hop stars like Mos Def, Kanye West, Dead Prez, and, reunited to ecstatic reception, the Fugees. Tireless funk musicians The Roots provide the backup for most of the performers, and the camera frequently finds drummer Ahmir '?uestlove' Thompson, who has towering hair and pounds away in an intense trance of rhythm.

Many of the big name stars talk about cutting their teeth in front of The Roots in their pre-fame club days, some reminisce about the schools they all went to within blocks of each other. And you see the performances – charged and angry and passionate, and you get a taste of something that’s raw, and came from somewhere real. Lauryn Hill sings an absolutely spine-tingling version of Killing Me Softly that starts with minimal accompaniment but grows with the power of her voice. The reaction of the audience to this, to Mos Def’s glowing charisma and hope, to Kanye West’s thrumming and apocalyptic Jesus Walks, is a palpable contrast to the processed and nutrient-free slurry which largely passes for rock and pop these days. If this generation has a Woodstock moment, it will happen at a rap show, and if you must pick one virtue to take away from this movie, maybe the chief one is that it dismantles the notion that all rap is just a monolithic gangsta-bling fantasy. There’s substance here.

Those expecting a feature-length “Chappelle’s Show” may be put off – his appearances are fleeting and off-the-cuff. You see him enjoying the spontaneous atmosphere, working the crowd, feeling his way to laughs using his natural timing and unerring post-P.C. straight talk. For one stretch he sits at a piano, noodling at “’Round Midnight”, exhorting viewers to listen to some Thelonious Monk, and riffing on the relationship between comedians and musicians. And gradually the guard drops, and suddenly he blurts – “I am mediocre at both, and yet I have managed to talk my way into a fortune”. Again, at a moment when he most firmly has our attention, he questions his worthiness to be its subject.

We walk around the streets of Dayton, Ohio, where he lives. He thanks shopkeepers for treating him like a normal person – he introduces us to local tailors and pizza parlors. And yet the common thread is – they all know he’s someone Big in the outside world, and their affection for him, genuine as it is, is colored by that. They can’t Un-Know it. He can reach out to them by distributing Golden Tickets good for a bus trip and hotel room in New York so they can attend the concert (a middle-aged woman amusingly worries about what to wear), he can even spontaneously decide to sponsor a college marching band to come join the show. And they all show decency and gratitude and excitement about the experience, but again, all of what’s unfolding is based on the premise that “Dave Chappelle” has become a superstar. He can no longer walk down a sidewalk without risking some stranger across the street yelling “I’m Rick James, bitch!”; and he’s wondering what to do about that.

This movie is messy, a little too long, jumps from mood to mood. Sometimes it celebrates the verve of the concert, letting you feel like you’re close to a moment of true creative conception. I like how it cross-cuts from rehearsal to performance as Chappelle works up a comedy bit where he tells corny jokes with disgusting punchlines while Mos Def drums and plays the straight man role. It fits the looseness of the event – planned enough that people are going to get a full bill of entertainment, but with wide spaces inside for spontaneity and magic to happen.

Then sometimes it’s content to play the Isn’t Americana Weird? game, zeroing in on bizarre personalities and recording their antics for our amusement. Though we stick with a few long enough to embrace them, I personally get uncomfortable with this sort of thing after too long. It’s a cheat in a country that’s not exactly lacking for people willing to goon around on camera. But when Block Party is its most engrossing as a film document, it’s about those precious couple of instances where we catch a man whose life has transformed even while he has not, and who determines to face that challenge with daring and humor. And the guts to put on a hell of a show and not charge admission.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Whitney Portal Road, looking down on Lone Pine, California

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - 16 Blocks

Originally published 3/4/06

Full review behind the jump

16 Blocks

Director: Richard Donner

Writer: Richard Wenk

Producers: Jim Van Wyck, John Thompson, Arnold Rifkin, Avi Lerner, Randall Emmett

Stars: Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David Morse, Jenna Stern, Casey Sander, Cylk Cozart, David Zayas

It’s been 18 years now since Bruce Willis staked his claim to superstardom in Die Hard, so he easily qualifies as an old pro by now. And director Richard Donner’s resume stretches all the way back to the 50’s, and classic episodes of The Twilight Zone. Remarkable that it’s taken this long for them to do a feature together, but the veteran savvy they bring to 16 Blocks makes it worth the wait.

Here we have a classic contraption thriller, a high concept with clear boundaries and rules that tests the filmmakers to deliver the goods while playing fair to the audience, and tests the actors to professionally essay their roles so they don’t turn into crash test dummies swept along in the kinetics. Its polish and success within those terms is a credit to Donner, Willis, an ingenious script by Richard Wenk, plus the performance by Mos Def in what is the key emotional role in the story.

You can see those 18 extra years that Willis carries around without concealment. Detective Jack Mosley is not the cocky and fit young Detective John McClain of Die Hard – he’s gray, he limps, his belly strains the buttons of his shirt, and he huffs and trudges everywhere like all he can think is that when he gets wherever he’s going, it won’t be any improvement on where he came from. Unless maybe there’s whiskey around.

But for all the physical differences there’s an important similarity to the two roles, one that lines up neatly with Willis’ star appeal over the years. He and his characters are at their best when they know they’re outmatched, when they don’t want this fight, because from a self-preservation standpoint it is not wise to carry on. But…but…but…something inside won’t let them walk away. Detective Jack Mosley is a man who hasn’t done the right thing in a long time, but today, for reasons we’re continuing to understand until the movie’s final minutes, some memory of how a cop is supposed to be swims up from his instincts and he acts on it.

At the end of a long night of thankless tasks he’s handed another, drive Eddie Bunker (Def), a kid in lockup, 16 blocks to the courthouse, where he is to testify to a Grand Jury and thus escape punishment from the charges against him. The Jury expires at 10 am – so if he doesn’t make it there, the case falls apart. And you don’t need to be a screenwriting guru to predict that there are parties interested in him not making it.

Eddie is a hard guy for Jack to like – he talks in a near uninterrupted rapid-fire squeak, and it’s a lot to ask of Jack to summon the focus and patience to even understand what he’s saying. The surface of Eddie is just another street hustler, another parole violator. But then Jack suddenly notices that Eddie has stopped talking, and it’s in that moment that Jack understands the stakes and the odds against him. And though he has every reason in the world to say it’s not his problem, to take a drink, to walk away and live for another day, he does what you want to see Bruce Willis do – but it’s in the body of Jack Mosley, so it’s going to be harder than ever.

Scattered around the urban jungle between them and the courthouse are a squad of crooked cops, led by Jack’s ex-partner, the amoral and silver-tongued Nugent (David Morse). These are not spring chickens, either, they’re middle-aged, overweight, mileage and experience on their faces. But it’s that experience that’s so dangerous – how many resources they have to track Jack and Eddie, how many ways they can conceal the truth, how swiftly they can converge on a building from all sides.

Donner never really pulls back far enough to give us a real sense of the geography involved – he stays street-level and tight. His intent is to not give us any better perspective than our heroes would have. And though it does verge on the ridiculous how little word spreads about the increasing carnage moving up the streets, since the movie plays out essentially in real time, you can almost believe that the sheer speed of unfolding events keeps ahead of it.

It’s a symphony of differing tempos – Jack’s gradually-melting lethargy (“We have to get to him before he gets his legs back under him” Nugent urges), Eddie’s manic neediness and ambition, and the contrast between frightening, sudden violence and quiet moments where the opponents stop to breathe and consider how to out-think each other in the next stretch. We progress through bars, crowded sidewalks, rooftops, a Chinese laundry, a commandeered city bus, and the clock just keeps ticking, and along the way we keep learning more about Jack Mosley’s career of ever-deepening shame, and the openness and optimism of Eddie Bunker. Mos Def proves himself, once again, to be the most delicate, creative and essentially sympathetic of rappers-turned-actors. If we didn’t look at him and demand of Bruce Willis – how can you not help him in his hour of need?, then 16 Blocks would fail as a movie. It succeeds.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Fountain Show, Bellagio Hotel, Las Vegas

Image Copyright 2005 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Firewall

Originally published 2/14/06

Full review behind the jump

Firewall

Director: Richard Loncraine

Writers: Joe Forte

Producers: Armyan Bernstein, Basil Iwanyk, Jonathan Shestack

Stars: Harrison Ford, Paul Bettany, Virginia Madsen, Mary Lynn Rajskub, Robert Patrick, Robert Forster, Alan Arkin, Carly Schroeder, Jimmy Bennett

I remember the first time that I saw Harrison Ford in a movie and thought he looked a little gray to still be running around clobbering evildoers. It was in the adaptation of Tom Clancy’s Clear and Present Danger – 12 years ago. I didn’t fret this, I’ve long admired Ford as an actor of undervalued restraint and professionalism, and thought this would simply open new doors for him to shuffle off those leading man heroics and embrace more of the nuanced work of which he was capable. And there were teases of how interesting this new phase of his career could be, like his turn as a husband with a few secrets in What Lies Beneath.

But there were more bad choices than good, and now he’s 63, a year older than Clint Eastwood was when he depicted himself as too broken-down to properly mount a horse in Unforgiven. And Ford’s still throwing elbows. And while I would never claim I could take him in a fight, as a movie critic I can say that in Firewall, Father Time is a far more formidable opponent for Ford than the criminals he’s matched against.

He plays Jack Stanfield, a hard-working security systems designer for a small chain of banks in the Seattle area. He lives comfortably in what looks like the exact same Canadian luxury home that Elektra plotted an assassination from, but it can’t be because his architect wife Beth (Virginia Madsen) designed it. She had enough foresight to design a crawlspace that has an escape door in the garage, but didn’t think far enough ahead to move the tool shelf on top of that door so one could actually use it for a discreet escape.

They’ve got two photogenic children, the abrasive teen Sarah (Carly Schroeder) and the moony 8/9-year-old Andrew (Jimmy Bennett). This makes Stanfield a pretty late bloomer, I guess he spent too much time on the computer for the first 40 or 50 years of his life. But if the offspring were off in grad school, they wouldn’t be around for a cold-blooded kidnapper (Paul Bettany) to menace.

Our kidnapper, who uses “Bill Cox” as his chief alias, is a student of modern enterprise, he believes in outsourcing. What better way to steal $100 Million from a bank than to hold a gun on the security designer’s family and make him figure out how to do it? This simplifies things for Cox, who need only spy on Stanfield and keep his armed men stationed at the house, though it leads to an unintentionally hilarious moment where the hoodlums stock the fridge with Hungry Man Frozen Dinners and menacing music thrums away on the soundtrack.

And so we get a Digital Age fusion of the family-in-jeopardy movie with a heist movie, with Ford as the Father-of-the-Year in the middle of it. We’ve got GPS tracking devices and camera phones and other Web-compatible trappings, but it’s still got to be about How Do We Get the Money and How Do I Rescue My Family? So bronzed is Ford’s heroic image by now that his character has nary an inch of emotional growth coming to him, his trial is purely one of keeping his wits, surviving multiple crippling blows to the head, and having enough gas left in his tank for the final showdown. And I have to say, for those who enjoy protracted, meaty pummel-fests at the other end of the spectrum from those insufferably pretty Matrix knock-off slow-mo ballets, the climax is a pip.

I think it’s the direction by Richard Loncraine, the British film/television craftsman who brought Ian McKellen’s Richard III to the screen, that is primarily responsible for the steady competence and momentum. Though the story has motions to go through and dutifully goes through them, there’s splashes of color that hint at a man looking through the camera and not wanting to see something totally generic. Like the very Seattle-specific apartment building where Jack’s secretary (Mary Lynn Rajskub) lives, or the nearly-invisible moment where Jack throws away an incriminating iPod, then reconsiders and reaches back into the trash for it, because he promised his daughter he’d return it. And the script by Joe Forte lets Bill Cox be something more interesting than the stock omnipotent mastermind, but someone who screws up, loses his cool, and is actively thinking ahead to stay on top of a plan that’s coming apart around him. It makes the cruelty he decides he must show much more chilling.

All of this is not enough, though, to shake the fatigue off the movie, because Ford is the center of the action. He does what is asked of him and is never less than believably distraught or determined or whatever else. But it’s his body and face that he can’t act his way out of. And they show a man who is over the hill and has Done This Before. Too many times.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

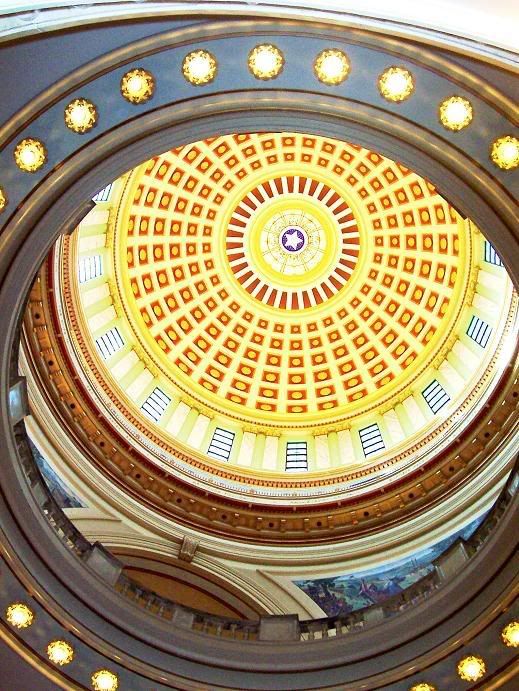

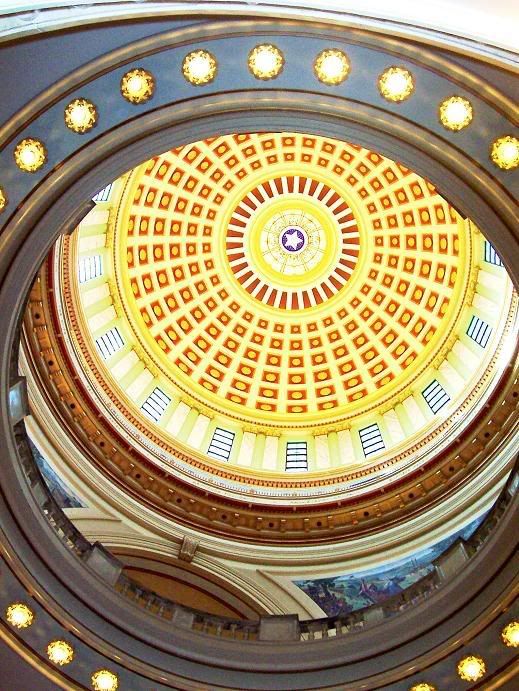

Dome of the State Capitol Building, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma

Image Copyright 2007 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Bloodrayne

Originally published 1/9/06

Full review behind the jump

Bloodrayne

Director: Uwe Boll

Writer: Guinevere Turner, based on the Majesco videogame series

Producers: Shawn Williamson, Dan Clarke, Uwe Boll

Stars: Kristanna Loken, Ben Kingsley, Michael Madsen, Matt Davis, Michelle Rodriguez, Will Sanderson, Billy Zane, Meat Loaf Aday, Udo Kier

I’m not sure if I can handle this becoming a tradition, but here we are for the second consecutive year with a movie adaptation of a video game, directed by Uwe Boll, released into the box-office hinterlands of early January. Boll has for video games the same tragic enthusiasm Lennie had for small animals in Of Mice and Men. He’s already filmed The House of the Dead and Alone in the Dark, and more are on the way. In mounting these productions so quickly Boll may be trying to ape the career of B-movie legend William “One Shot” Beaudine, who directed gaffe-infested cheapies like Billy the Kid versus Dracula and Bela Lugosi Meets a Brooklyn Gorilla, and whose shooting technique needs no further explication.

The best I can say about Bloodrayne, today’s exhibit, is that it is not, from first frame to last, as staggeringly incompetent or incomprehensible as Alone in the Dark was. Most of the time it is simply silly. For Boll this is progress – though not always in sensible order the scenes which seem to belong near the start of the movie do so and ditto the end. From there it’s hard to find positives: the visual effects are forgettable, the combat unremarkable, the story derivative when you can actually follow it. The costumes are Ren-Faire hand-me-downs and the sets look ready to collapse if bumped into; the budget is listed at $25 Million, and I suspect $22 Million of it was smuggled away in laundry bags. You can’t expect much bang for your buck in early January. You can still ask for more than this, though. A lot more.

The game, by Majesco, is only middlingly-popular and not too highly regarded, though it sold well enough to merit a sequel. I suppose the box cover made the case for adaptation – a bosomy redhead in black leather with vampire fangs and two giant blades. It reminds me of the scene in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood when the cult filmmaker is applying for a job, asks “Is there a script?”, and the distributor snorts, “F*** no! But there’s a poster!”

The background is not much more than Blade with mammaries: Rayne (Kristanna Loken of Terminator 3) is a dhampir – half-human, half-vampire – who allies with a secret group known as the Brimstone Society to combat evil. Because sucking blood is okay, even kind of hot, if you’re doing it to bad people. The games took place in World War II and modern times – inexplicably, this version is set in an unnamed Eastern European country in an unidentified but sort-of-swashbuckling era: call it Romania-esque in the 18th-or-maybe-early-19th century. Most of the characters speak American-inflected English, they just drop the contractions and hope we’ll consider it refined.

Anyway, far outside some village in Romania-esque, the orphan Rayne (wearing the kind of bustier and lowriders-with-lace-up-crotch combo you see models wearing at Comic-Con) is an unwilling participant in a carnival freak show, tortured so she can display her amazing ability to heal after drinking a few drops of animal’s blood. Her vampiric side hasn’t awakened yet, but will when she finally tastes human vintage. And, at some point while she’s off camera, she decides that she only wants to kill vampires and their allies.

The blank spots in her life story are filled in by a gypsy fortune-teller played by, of all people, Geraldine Chaplin, daughter of Charlie. When asked why she’s providing all this exposition, the fortuneteller replies – “It’s my purpose!” At least she’s honest. Rayne, it turns out, was conceived by the master vampire Kagan (Ben Kingsley), who raped and murdered her mother and is just this very moment hatching a scheme for world domination that involves collecting magic doodads that will make him invincible...or something to that effect. Kingsley spends at least 2/3 of his screen time sitting very still in his throne while underlings enter with announcements like “I have brought the Talisman!” To which he’ll bark “Excellent!” and the scene ends. I’m thinking they knocked out all the throne scenes in about a half-day, but he does have time to add a subversive touch or two: I like the wanly-reassuring smile he offers a girl brought to him as lunch.

This is a pattern for the movie, wherein people of dubious celebrity appear very briefly with self-contained opportunities for scenery-chewing. Billy Zane ponces around in a wig for a few minutes in a role which, if you think about it, has nothing to do with anything – the opening credits announce it as a “Special Appearance”, like an episode of The Love Boat with spraying wounds. And Meat Loaf Aday ups the ante with an even bigger wig and a harem full of naked women. I did laugh at his domicile, where peasants are chained to the ceiling and their blood is drained into mugs like the office water cooler, but poor Loaf proves what isn’t but should be an old adage: creatures who melt in sunlight shouldn’t include so many windows in their house.

None of them look like they know what’s going on, or that they care – they are in the movie not because they can pass themselves off as citizens of Romania-esque, but because they matter to some foreign-financing calculus. At least they exit stage left fairly rapidly, Michael Madsen must navigate the whole movie as Vladimir, vampire hunter and local head of the Brimstone Society. Members wear easily-identified necklaces but are, nonetheless, very very secret. He pauses after every fourth word, like all his dialogue is coming through an earpiece from a UN interpreter. He finds Rayne, decides she can be trusted, and takes her to Brimstone HQ for training. The movie needs him since Rayne spends most of the movie walking into stupid traps or being captured or knocked unconscious.

There’s umpteen shots of horses thundering across landscapes. Left to right, right to left, sometimes kind of diagonally-upwards. Sometimes it takes a second to remember who it’s supposed to be on the horse, since they vary in number and thunder through landscapes of the most bamboozling randomness – mountains and cliffs and plains. What’s remarkable is how consistently un-breathtaking any of this scenery is; though filmed in Romania, which you’d presume has an evocative angle or two, most of it looks like it was shot just off an interstate.

Not much of Bloodrayne makes sense. In one scene, a monk (Udo Kier) tells Rayne it’s not safe for her to leave, since Kagan’s army of followers are searching for her. Then that army pillages the monastery, and the monk realizes his suggestion had a downside. Vladimir’s sidekick Sebastian (Matt Davis) takes great care to bring a bottle of “holy water” with him into battle, although this movie suggests vampires are averse to all water, so I’m not sure to what greater use holy water’s supposed to be put. Sebastian has the great fortune to happen upon Rayne when she’s feeling a different sort of hunger, and they go on to prove what should be an old adage that any sex scene which spends more than a minute trying to look passionate ends up looking funny instead.

Maybe I can come to an inner peace over the career of Uwe Boll – he puts people to work who might otherwise be loafing around the house, and his movies are easy to review because they contain so many clanging “What the Hell?” moments. They’re an entertaining sort of awful, at least to a masochist geek like m’self. But I also passionately enjoy both movies and videogames, so I must hope that he doesn’t apply his uniquely-destructive aesthetic to too many more. Pitfall Harry has suffered enough.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Shasta Lake, Northern California

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Tsotsi

Originally posted 2/24/06

Full review behind the jump

Tsotsi

Director: Gavin Hood

Writer: Gavin Hood, based on the novel by Athol Fugard

Producer: Peter Fudakowski

Stars: Presley Chweneyagae, Mothusi Magano, Zenzo Ngqobe, Kenneth Nkosi, Rapulana Seiphemo, Nambitha Mpumlwana, Terry Pheto, Jerry Mofokeng

In the end Tsotsi (Presley Chweneyagae) will cry, but I think it’s not from sadness. It’s exhaustion, because he’s finally stopped running. At nine, as his mother lay dying from a plague still misunderstood in much of Africa, and his father raged with drink and abuse (and, perhaps, his own complicity in his wife’s condition), he ran from home. He ran away even from his name, and now the name he gives himself means “Thug” in the mishmash street language of the Johannesburg slums. And when he steals a rich woman’s car (Nambitha Mpumlwana), shooting her in the belly before he has time to contemplate why she’s so desperate to get back in, the discovery he makes prompts renewed flight, because the woman’s baby is in the back seat.

These are the broad circumstances of Tsotsi, Gavin Hood’s adaptation of an early novel by the acclaimed playwright Athol Fugard. It is South Africa’s submission for the 2005 Foreign Language Film Academy Award, and it’s easy to see why it was rewarded with a nomination, as its fable-like structure and ability to communicate in universal emotions transcends language and creates a deeply-felt movie experience. You don’t need to understand South Africa, you just need to understand being poor and without hope.

Tsotsi commands a street gang now, young and with murderous intensity. We watch as, with pitiless silence, a mugging becomes a killing right in the middle of a packed subway car, and the bodies are so close together that the corpse does not fall until the train empties at the station. He lives in a one-room shack with a corrugated roof – to reach it he must climb a jagged pile of concrete and rubble. The radio he dances to runs off a car battery. This is an improvement in his circumstances, we see that after running away he essentially grew up in a concrete pipe. A pile of them sits on a hillside – perhaps abandoned with a long-ago construction project, they’ve been neglected for so long they’ve become an ad hoc orphan community where the 12 and 13-year-olds are the parents. Visiting it again, he points the upper-left pipe out to the current tenants and says “That one used to be mine”.

In this way the film is reminiscent of the South American City of God, paying keen attention to the slums – so close to the prosperous city they can gaze on its towers, and within a teeming mix of poverty, color, music, crime, drink, despair, ambition and struggle. As chaotic as it is there’s life here. Hood does not show the flair of City’s Fernando Meirelles, but he has different ambitions – more focused in story and broad in theme.

When does Tsotsi make the decision to take the baby? Is it when he first gets out of the car, ready to abandon it? Surely there was no thought of returning it – by necessity the habits of his life have been to never go back to the scene of the crime. Before he found himself with a baby to protect, Tsotsi knew only how to get what he needed at the end of a gun or shank. He tries this still, even trying to get breast milk with his pistol. But this and many other encounters over the next few days force a change in his outlook. This quirk of fate has unlocked memories he’s refused to face, and reacquainted him with choices he forgot were available.

And as all this goes on, the frantic, crippled mother and her husband (Rapulana Seiphemo), who yearns to give her hope but knows the odds, watch as a police investigation proceeds with professionalism, but agonizing slowness. Having seen from every angle the urban jungle Tsotsi and the baby have vanished into, we know without the cops needing to say it just how difficult this search will be.

It’s a sign of confidence that a young filmmaker can allow so much range of tone and pacing in one movie. You not only have the jittery energy of the streets (the soundtrack is propulsive), but quiet, almost contemplative vignettes where Tsotsi meets one after another in a parade of characters, and the way he responds to them at the beginning of the movie is far different from the end. The film speaks in simple gestures and situations, and it might sometimes feel awkward or heavy in doing so, but when you see how such simple needs and motives can pile on one another to create a home break-in charged with potential catastrophes, it’s a tribute to Hood’s storytelling chops.

I think as audiences we urgently need to believe that heartless characters can be redeemed, and that some needs (the love of a mother, the vulnerability of an infant, the struggle to find a place in the world) are so fundamental they overpower pettiness and anger. The feelings those things stir are the feelings you will leave Tsotsi with.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Downtown Chicago

Image Copyright 2006 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - The Matador

Originally published 2/23/06

Full review behind the jump

The Matador

Director: Richard Shepard

Writer: Richard Shepard

Producers: Pierce Brosnan, Beau St. Clair, Bryan Furst, Sean Furst

Stars: Pierce Brosnan, Greg Kinnear, Hope Davis, Philip Baker Hall, Dylan Baker

“Delight” is the only word that can describe my reaction when Julian Noble (Pierce Brosnan) shows up on the quiet suburban doorstep of Danny Wright (Greg Kinnear). And it’s not just because I was ready to see their unusual and entertaining bond perpetuated, it’s because of something rare which happens. You see, Danny is a straight-arrow businessman, and Julian’s a freelance assassin. They know each other from a wild weekend down in Mexico, where some things happen that you wouldn’t always tell the missus about. And when Julian comes through the front door, Danny’s kind and patient wife Bean (Hope Davis) knows who he is and what he does.

Can you see what I’m getting at? Maybe you have to imagine the tiresome gymnastics which would have ensued in any other movie – where Danny would have sputtered and fretted and hidden the truth, and the movie would grind to a halt in a series of embarrassing falsehoods and convolutions about who Julian is and why he’s acting like Danny’s best mate. But Richard Shepard’s The Matador presents us a marriage built on real trust and honesty, and so skips that pitfall; in fact, skips around so many of the usual traps its rather precious narrative might have fallen into – and with confidence and frisky humor asks us to accept one simple premise: that Danny and Julian met in a bar, and liked each other. Here is a movie more interested in tone, nuance and character than subordinating everything to another heartless exercise in plot, and it’s a pleasure to witness.

Set aside his grisly profession and you might recognize someone you know in Julian – he’s a friend most everyone makes at some point in their lives. The one who drinks too much, makes inappropriate remarks and even more inappropriate propositions, because he is drunk; and then, late in the night when he’s even more drunk, feels very very sorry about what he did earlier and wants badly to tell you about it, even if you’re trying to sleep. His need for any real contact is palpable, painful – he’s a shambles of a human being who’s lived out of hotel rooms for over 20 years. He kills someone, he gets paid, he drinks, he screws, and he moves to the next town. To him, a man like Danny, with a wife and a tasteful house and an SUV, is Superman.

But for a shambles he’s a hell of a good time – funny, mischievous, full of entertaining stories. Sooner or later everything reminds him of Asian hookers. Both he and Danny are in Mexico City on “business”, and both are sipping margaritas in a hotel bar late one night, and the audacity of Shepard’s work creating these characters is to convince us that each needs something the other can provide, and so no matter how challenging it is for them to find common ground in their lives, neither can quite let go of their contact with the other.

Danny doesn’t believe at first that Julian really kills for a living. Then, at a crowded bullfight, Julian walks him through exactly how he’d snuff out a randomly-chosen person, and in the midst of Danny’s enjoyment of it all it stops seeming so preposterous. It does not end up how you’d expect, but then, little in this movie does. You keep expecting it to be about a conflict, some terrible deadline or moral conundrum. But instead, for much of its length, it’s cheerily content to be about the possibilities of a heartland American couple accepting someone like Julian as a human being. Danny even describes him to Bean as “nice…you know…for a hitman.”

Bean is just as friendly, and fascinated, and if you think you can see where it would go to have an attractive woman under a roof with Greg Kinnear and Pierce Brosnan, you’ll again be disappointed. This is a solid marriage, I’d near say an inspiring one, that has weathered fourteen years of tragedy and struggle yet still can give over to a naughty mood in the laundry room. How often has a filmmaker written simply that – two people who don’t give in to easy jealousy or misunderstanding, who have just made it work together?

Of course, their success is the greater highlight to Julian’s failure – his functionality is so reduced that he’s beginning to botch jobs. And his is not a forgiving profession for those past their prime. Now that he’s left behind the supremely confident James Bond role, that Brosnan is free to take on a character so humbled, so hilariously corrupted and ruined, is a treat for audiences and a tribute to the adaptability of his screen charisma. Kinnear, too, finds the right notes in the enriched straight man role, and Hope Davis carries on her tradition of making the charming most out of every second on camera. She unerringly finds the precise moment to delight us with another dimension to Bean, the high school sweetheart who believes in her man. She’s good enough that when the two-man show becomes two-men-and-a-woman, not a drop of chemistry is lost.

If it seems like I give too much away, I’m sorry – I’ve tried for the most part to reveal to you what the movie is not. Those less-traveled roads it does take I hope you will discover and delight in as I did. The Matador is a compact picture, exact in its intentions yet breezy and fun in delivery. It blends comedy and violence and pathos, and moments of naked honesty, and makes a sweet cocktail of it. “Margaritas always taste better in Mexico” opens Julian in that fateful bar. Danny agrees, and I wouldn’t dream of spoiling Julian’s follow-up.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Depoe Bay, Oregon

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Transamerica

Originally posted 2/7/06

Full review behind the jump

Transamerica

Director: Duncan Tucker

Writers: Duncan Tucker

Producers: Rene Bastian, Sebastian Dungan, Linda Moran

Stars: Felicity Huffman, Kevin Zegers, Fionnula Flanagan, Elizabeth Peña, Graham Greene, Burt Young, Carrie Preston

It’s truly remarkable how the world of independent film has evolved in the past 15 years. As subject matter has widened, so has the polish and structural awareness of the filmmaking. Where it was once the place for stylistic daring or non-traditional storytelling, many “independents” are now simply inexpensive variants of the same Hollywood formulas. And for subject matter, what once was fringe is now moving into the mainstream, allowing more unusual fare to take prominence within the fringe. So you can have a handsomely-produced homosexual love story like Brokeback Mountain starring A-List talent and filmed by an A-List director, while back in the churning fringe we now have a capable and engaging, often funny (but gently so) movie, Transamerica, about a transgendered person.

A transgender is not homosexual – they have a preference for the opposite gender to themselves. It’s their definition of what gender their “self” is which is at odds with the body they were born into. And while this is a challenging concept to some audiences, it is delivered in a vehicle that, without that added twist, would not leave a lasting impression. The bonding road trip – where two people bridge the wide chasm between them while crossing through postcard landscapes and meeting an eccentric cross-section of Americans in a beat-up car – is hallowed, creaky even. And writer/director Duncan Tucker’s script is a square and even sometimes awkward assembly of convenient conflicts and sketch-simple characters. Its greatest asset – what makes it worth recommending in spite of all – is the central character of Bree Osborne, as realized by the Oscar-nominated Felicity Huffman.

Bree came into this world with the name of Stanley, but rejected this label as she rejected her own organs. Deep inside herself she knows, simply knows, that she is a woman. And with the painful procedures she’s already undergone – hormone treatments and hair removal and facial surgeries and on and on – she’s demonstrated more commitment to this knowledge than anything else in her life: she spent ten years in college without earning a degree and lives in a humble Los Angeles bungalow while juggling waitressing and telemarketing.

She is prim, polite, even sort of dull in her insistent fussiness. Her voice is a level alto, breathy because it would be low if she weren’t exerting an effort. Her body language is distinctly feminine, not pronounced as such (she has no desire to stand out, she lives as a “stealth”, faking her gender until the surgical transformation can be completed); but, if you were looking closer, you’d see a heightened awareness and effort, because it’s man’s body that would walk like a man’s without the effort. Consider the dexterity required of Huffman, who must act her own sex as if coming to it with observation but no direct knowledge, and you see why she deserves not only to be considered for this year’s Best Actress Academy Award, but to win it.

She is one week from the decisive surgical procedure which, euphemistically speaking, will turn her “outie” into an “innie” – at which point she will be, even by the medical definition, 100-percent woman. Her intense anticipation of this day is interrupted by one fateful phone call from a police station in New York.

She has a son. Or rather, “he”, while still living as Stanley, impregnated a woman in college, never found out about it, and the son is now seventeen and hustling on the streets of the Big Apple. The mother is dead, so the police called the father, who really doesn’t want to be thought of in that way. She wants nothing to do with the boy, who sounds like trouble, but her therapist (Elizabeth Peña), whose signature is required for the operation to go forward, now threatens to withhold that signature if Bree doesn’t face this drastic upheaval in her life.

Okay, it feels arbitrary, but it gets us where we’re going, as Bree travels to New York, bails out the handsome but surly young Toby (Kevin Zegers), and, not ready to explain his novel parentage, poses as a social aid worker from a Church. He’s an unrepentant drug user and yearns to move to Los Angeles to break into the gay porn industry. Which makes them like the Odd Couple; but with cocaine, illicit truck stop sex and a battered old station wagon packed full of hidden truths.

Bree, per the demands of her role in the script, seeks every opportunity to discharge this rude kid, but is each time, per the requirements of the story’s forward progress, unable to. And somehow they stay stuck together through their coast-to-coast odyssey, and against their will they learn about each other and come to depend on each other.

Without Bree in charge, and the way her circumstance manages to create unique needs and misunderstandings, this drive would hardly be worth the taking. Tucker succumbs readily, eagerly even, to soap opera tactics – characters drawn to the broadest of extremes, and in dialogue, hurling skeletons out of theirs and each others’ closets with tactless and unbelievable abandon. Outside of Bree’s determination to complete her evolution into womanhood nothing feels organic or lived through, just slapped together from other movies. We meet Bree’s family, and it’s only the deftness of actress Fionnula Flanagan that keeps the mother she portrays from being an unwatchable horrorshow of scorn and judgment. Watch the scene where she processes one pulverizing shock after another, then finds one fact in the whole perverse situation that appeals to her and seizes on it – this is an actress doing her level best to flesh out a narrow role.

But maybe this is necessary disguise for the movie to reach a wider audience – the “stealth” of a familiar genre smoothing the way to a greater understanding of a little-discussed subset of our population. If it’s not too backhanded of me I can compliment Tucker on his familiarity with the basic levers and gears of Hollywood feel-good. It’s the richness of Bree, though, so distinct, so fully in the flesh, that shows the rest of Transamerica to such disadvantage – I want the quirky and colorful surroundings worthy of her and her journey.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Turns out there was no problem with Photobucket, my Firefox was just sulking until I closed it so it could update.

With all the yellow heat in the sky today, we could use some cooling Pretty:

Path to Munson Creek Falls, outside Pleasant Valley, Oregon

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - The New World

Originally published 2/7/06

Full review behind the jump

The New World

Director: Terrence Malick

Writer: Terrence Malick

Producer: Sarah Green

Stars: Colin Farrell, Q'Orianka Kilcher, Christian Bale, Christopher Plummer, August Schellenberg

Terrence Malick does something I really like at the end of The New World, his meditative observation on the founding of the Jamestown colony and the unusual life of “Princess” Pocahontas (Q’Orianka Kilcher). I’d tell you about it, but I’m not in the habit of describing the very ends of movies in these reviews. You will have to decide if it is worth traversing the beginning and middle to reach a rather lovely conclusion, because for many it will be something of a trial.

Film-lovers will have some preparation for the experience of a Terrence Malick picture. With every project he retreats further from the niceties of plot and traditional storytelling, and delivers instead an extensive idyll preoccupied with the rhythms of nature and communicated through furtive inner monologue. More dialogue occurs between the ears of these characters than ever passes from their lips.

Here it is sporadically hypnotic – we are watching a de-glamorized, straight ahead depiction, filmed largely with natural light, of a historical moment. Not the arrival of explorers – America was already identified and labeled a place of opportunity – this is the landing of a different expedition, one that intends (after a grueling voyage) to stay and set up shop. And so the question of whether their culture can co-exist with that of the “naturals” already on the land can no longer be avoided.

There is love in this story, though it is not a “love story” in the traditional sense. It does note that John Smith (Colin Farrell) – a tough and insubordinate soldier who nearly becomes America’s first hanging victim – is captured by tribesmen while attempting to establish trade and is ordered executed by Chief Powhatan (August Schellenberg), and that he only survives because the Chief’s favorite daughter (Kilcher) throws herself on his body in protection. But you might best describe their relationship as one of passionate curiosity, one that certainly extends to the physical, as Smith shares the English words for various facial parts, and his smile tells us where this conversation may move next.

But it does not end here – it continues through dissension in the Jamestown colony, a savage winter, armed confrontations, the price Pocahontas pays for her affection for Smith and kindness to the white man in general, and even the rather cold-hearted way their relationship comes to an end. She ends up with another man, a second-wave colonist named John Rolfe (Christian Bale) – who shows her respect and sensitivity and loyalty, admires her and protects her in a way closer to what we’d recognize as a courtly Western love. And from her time with the people of Jamestown, the “Princess” (re-christened ‘Rebecca’) comes to recognize and appreciate this love, even though part of her still pines for the romantic sense of discovery she felt with Smith.

The movie doesn’t really take sides, except maybe the side of the trees and rivers: the natives see them as shelter and source of food, the colonists as building material and transport. Malick takes long, languid opportunities just to regard this primitive wilderness, so as to invite us to imagine the mystery and seduction it held for those Europeans. For all of his and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s skills, though, you will find yourself glancing at your watch after one too many shots of water ripples, one too many lines of ambiguous voice-over. “He is like a tree” – this is how Pocahontas describes husband Rolfe, and the simile is more airily juvenile than poetic, and the more frustrating in how little it tells us about either of these two important characters.

The colonists are blindsided by the harsh conditions of Jamestown, but the movie notes the toughness and adaptability they show when tested. When the snow clears they’re still there, with more boats on the way. And while Smith is initially enraptured by the Native American culture, ascribing to it a kind of holy perfection, we in the audience see a more divided, complex and interesting civilization.

It takes restraint to not fall into the usual pastoral trap of making this the myth where the pristine “Indians” are corrupted and destroyed by greedy and disrespectful scavengers. The New World goes deeper – using an expansive and thorough view of the details to show that the gulf between these peoples was too unfathomably large for conflict to be avoided. When “Rebecca” sails for England for an audience with the King, her father sends an observer/bodyguard, who carries a bundle of sticks and instructions to notch one every time he sees a white man. When he steps off the boat in England, beneath his stoic expression you can detect a man realizing he doesn’t have enough sticks.

How do you bridge gaps in understanding like that? On the personal level, John Smith and Pocahontas found a way for a short time at least; but Malick’s point, if he has one to make, is that the problems of two little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this New World. Towns, colonies, kingdoms, these are more complex organisms, and their meetings are fated to be more cataclysmic. Like with our two leads, these two cultures first felt an intense and generally benign curiosity, but unlike our leads the cultures continued to co-habitate and the differences gradually took prominence. This is near to the heart of this story’s longevity, I think – but in the hands of a filmmaker so diametrically opposed to the emotional mechanisms of cinema we never feel a charge from it. The New World offers gorgeous scenery and authentic grime, and you’ll enjoy looking at it, and hearing the chirping-buzzing tapestry of nature sounds that accompany it. But in the final analysis it is not the transporting experience it could be.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

O'Hare International Airport, Chicago

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Match Point

Originally published 1/5/06

Full review behind the jump

Match Point

Director: Woody Allen

Writers: Woody Allen

Producers: Letty Aronson, Lucy Darwin, Gareth Wiley

Stars: Jonathan Rhys-Meyers, Scarlett Johansson, Emily Mortimer, Matthew Goode, Brian Cox, Penelope Wilton

First, you’ll have to let go of the fact that this is a Woody Allen film. It’s possible to forget once you start watching. It is not a comic treatise about the failure to get laid, it does not feature a May-December romance. When characters discuss art and literature it is the background to much more urgent tensions. It does not take place in New York.

So what is Match Point, and why am I recommending it far and wide, to fans and non-fans alike? Well, besides an expertly slow-bubbling thriller, besides a lacerating study of guilt, class and hypocrisy in love, it is also Allen’s most successfully serious picture, and his most potent examination of self-justifying, self-deluding amorality, since 1989’s Crimes and Misdeameanors. And this story doesn’t even have the misdemeanors to lighten the mood.

It is also, this surprising film, this bursting of a great filmmaker out of a cocoon of underachievement, his most grown-up treatment of sex in at least as many years. This is clutching, and breathing, and fabrics tearing, miles away from the comic underdog on the make. If the stereotypical Woody Allen protagonist is the desperate neurotic who can’t keep the girl interested, that image is quickly washed away by Chris Wilton (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers), who certainly can interest the girl; can in fact, have anything he wills himself into, including a life of status and fortune. His crisis comes, as it does in the good stories, when he wants two things and cannot have both. But until then his cool ambition, his predatory drive, give Match Point a throbbing life you might have forgotten was possible from the one-time stand-up comic who once had Howard Cossell on screen providing expert analysis of a roll in the hay.

Wilton was a professional tennis player – it’s said that had luck bounced a few balls the other way, he could have lodged victories against some of the world’s best. He does not miss the grind or travel, and happily takes a job giving lessons at a veddy exclusive club in London. At night he reads great books, then other books that will help him understand the great books so he can impress people with the fact that he understands them.

At this club he meets Tom Hewett (Matthew Goode), a rich and handsome young layabout whose primary interests lie in disappointing his father (Brian Cox) and mother (Penelope Wilton). He might be an alcoholic three years down the road, but for now is functionally happy-go-lucky. It probably comes from his mother’s side. He invites Wilton to lunch and the two have a politely pro forma duel over who will pay.

And thus begins a calculated trip up the British social ladder for the low-born and Irish Wilton – who has lavish gifts and posh invites sent to him because he insists on making his own way, who woos Tom’s sister Chloe (Emily Mortimer) by constantly pointing out how beneath her station he is, and who wins a position with room for advancement at the senior Hewett’s company by declaring his distaste for handouts. And because he is polite, handsome beyond measure, well-spoken, and particularly because he is so charmingly reluctant to accept all these bounties, his circumstances improve with whiplash speed.

But there’s that other thing I mentioned that he wants, and that is Nola Rice (Scarlett Johansson), a sensuous and emotional struggling actress from America who is engaged to marry Tom. She smokes too much, becomes flirtatious when drunk, is well-aware of her effect on men and torn about the balance of its advantages and disadvantages. She most definitely does not meet with Mother’s approval. Wilton becomes desperate for her even as he’s steadily approaching the altar with Chloe, and the magnitude of what he is risking to have her – all the fruits of his master plan – cranks up the heat of the movie’s second half by agonizing degrees. It becomes, literally, a matter of life and death, and you will be astonished to find, in a late scene, that someone who has done something horrible is about to mess up and be caught, and you are not cheering it along but are in fact very tense. Think for a moment of the talent and storytelling confidence it takes to ferry an audience to a moment like that.

Something that will be familiar to Woody Allen fans is the sharpness of the dialogue, how it can breathe truth into the empty spaces between banalities and how precisely it can articulate attitudes. He can have characters use flat banter, know it is flat, and have more interesting conversations with their eyes and bodies as they talk. He knows that sometimes characters talk to get what they want; and at other, more interesting times, they’re talking to build themselves up to a point their heart would tell them shouldn’t be approached.

I think it’s the new environment that wakes up his attentions as a filmmaker. This is new slang, new streets, new theatres and art galleries and restaurants for his characters to prowl as they work their needs out on each other. Even the performances have a vibrant attentiveness beyond the best of his recent work, because they are not larger-than-life eccentrics like Sean Penn’s vulgar guitar genius in Sweet and Lowdown, but people you’ve seen shopping at the better stores. Rhys-Meyers and Johansson each have their own vocabulary for smoldering, and to see it turned on each other is to see an all-consuming conflagration due to break out at any second. And there is humor, but the kind that comes not in punchlines but in seemingly perfect moments of observed behavior.

You still get the traditional quick-fire opening credits in the old-fashioned typeface, the cast listed in alphabetical order while an old gramophone hisses behind. But this time it’s not the old jazz, it’s opera, the whole soundtrack – Verdi and Rossini and Bizet. Not only has Allen moved his aesthetic to a different continent – the project has a distinctively European vibe to it, add more breasts and smoking and you could have filmed it in French – perhaps even more tellingly, he’s moved to a different area of his record collection.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Convict Lake Campground, outside Lee Vining, California

Image Copyright 2005 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - Munich

Originally posted 12/23/05

Full review behind the jump

Munich

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Screenplay by Tony Kushner and Eric Roth, based on the book Vengeance by George Jonas

Producers: Kathleen Kennedy, Colin Wilson, Steven Spielberg, Barry Mendel

Stars: Eric Bana, Daniel Craig, Ciarán Hinds, Mathieu Kassovitz, Hanns Zischler, Ayelet Zorer, Geoffrey Rush, Gila Almagor, Michael Lonsdale, Mathieu Amalric, Moritz Bleibtreu

I think Avner (Eric Bana) has an instinctive sense for what is really being asked of him. I think his mistake is in thinking he can undo it, that the uniform for this particular job he’ll be able to shed before he comes home to his wife (Ayelet Zorer). The job – handed down by his bosses at the Mossad (the Israeli special forces) and his boss’s boss’s boss, the Prime Minister Golda Meir (Lynn Cohen) herself, has strategic value, as it is always smart self-preservation to seek and eliminate those who threaten your existence. But to fulfill this job will require him to give up his humanity and become an instrument. He will embody, internalize, live the response of a nation (not a religion, this is key) to a tragedy that can be summed up in the word Munich.

The consequences both personal and political are in the sights of director Steven Spielberg, who is here attempting the most difficult film of his career. In the beginning he dramatizes the incident, not as keenly felt or understood to the generations who’ve grown up since, where a Palestinian terror cell kidnapped and murdered 11 Israeli athletes in front of the eyes of the world at the 1972 Munich Olympics. He does it with such easy urgency, such casual technical virtuosity, you can forget in the standard we hold him to how fluently he sends his camera into chaos to find the feeling.

And what for another filmmaker would be a triumph – sharp and harrowing – is for him but a starting point, an entry into a story that’s both epic and nebulous, charged with a sense of right and wrong but refusing to supply a simple hero or villain. It is not out to tell us how to solve a problem, it is a long gaze at an open wound, a 164-minute cry of mourning; operatic, and so exceeding its grasp in moments, but still a film I can’t think anyone else would have the facility and daring to attempt.

In the aftermath of the attack, the leaders of Israel gather. They have 11 dead – they select 11 targets. All of them had at least peripheral roles in the attack, from communications to financing, but no one in the room has to articulate why this particular number has been chosen. An eye for an eye has become a matter of policy.

Avner, a good soldier, formerly Meir’s bodyguard, will disappear into the European underground and lead a squadron of assassins to find and kill these 11 men. They will have no official connection with Israel (he has to sign away his health insurance), but will receive unlimited funding via a safe deposit box in Switzerland. This is a tricky balancing act – the state can deny complicity, and yet Avner is advised by his handler Ephraim (Geoffrey Rush, virtuosically combining bureaucratic tetchiness with menace) that guns are fine, but explosives are ideal, as they are visible and instill fear. Israel wants fear, they want the message spread that violence will be answered, but they also want plausible deniability. And so they join the modern fraternity of nations at war with each other while pretending they’re not.

Avner’s team is gunman Steve (Daniel Craig), document forger Hans (Hanns Zichler), clean-up man Carl (Ciarán Hinds), who when asked what his specialty is, answers “I worry”, and Robert (Mathieu Kassovitz), who makes toys for a living, used to help dismantle bombs, and now has been asked to build them.

And as each killing is methodically planned (these sequences provide a sickening thrill) the team becomes – a unit? A family? They do dine together, Avner cooks for them, it might be a means of clinging to normalcy. Certainly they share a common if conflicted mind; it’s as if the conversation revolves and someone must always be the agitator, the doubting one, the reflective one. One character inflicts a gruesome gesture of pique on a dead body over his colleague’s objections. Later he says he wishes he’d let himself be stopped. We don’t get many details on any of the characters, but casting goes a long way – these are all faces that have stories behind them.

The question is raised whether their peoples’ suffering has made them noble, or whether it was the righteousness in the face of the suffering. But more pragmatically, considering the body count of the Holocaust and the equally-terminal rhetoric of the terrorists and their extremist apologists, can they survive much more of this suffering without fighting back? And what happens to a spiritual man who must sin, not for his own survival, but because he believes it contributes to his peoples’ survival?

Globally, Munich is about people on all sides of a conflict who believe with such passion that they may never find common ground, and it is also about the consequences of blurring the line between a religion and a state. I think that Spielberg’s Schindler’s List was about Jews, a people threatened with extinction, whereas this film is about Israel, a nation figuring out how to defend its borders from its enemies when its enemies come not armed with tanks but numbered accounts and European safe houses. When Israel took on the protections of having their own nation, they took on the complications as well, which includes gut-checks about whether you are the kind of nation that sends assassins into countries you are officially friends with acting on evidence that may or may not hold up in court.

And within all these big questions is a head-spinning piece of cinematic paranoia. Charged topics aside it could be isolated as a triumph of morally-gray espionage on a par with The Spy Who Came in from the Cold or any other movie of its kind ever made. Avner’s crew must navigate allies who cannot be trusted, information that may be coming with a different agenda behind it, and the unfathomable layers of conflicting national interest. There’s tragic absurdities too, like the uncomfortable night Avner’s crew must spend in a safe house which is, for lack of a better word, double-booked.

They lie to people who expect to be lied to, are lied to in return, and money changes hands and jobs are accomplished, though not without their hair-raising moments of spontaneity. Avner is taken into the nominal confidence of a French information broker called Papa (Michael Lonsdale) and his son Louis (a smooth and excellently enigmatic Mathieu Amalric) – they claim to despise governments and refuse to deal with them, and yet accept Avner’s flimsy cover story because he pays well and on time.

There’s little need to address the acting, which is superb, or the physical aspects of the production, which are flawless under the very difficult circumstances of a globetrotting period piece. Your reaction will be determined by what you decide Spielberg is saying and how that moves you. I think the pat and lazy interpretation is that Spielberg has suddenly discarded his heritage and embraced moral relativism. As unlikely as that is on its face (really, the maker of Schindler and the founder of the mammoth Shoah project suddenly plopping himself down on the fence?) it’s also unsupported by the evidence.

I believe that in this flawed but deeply felt movie, one of the most impressive of the year no matter your opinion of its politics, Spielberg is not out to condemn. But nor is he out to conceal – he shows that Palestinians have unjustifiably killed innocent Israelis, and that Israelis have struck back and there has been what is coldly labeled collateral damage, but really means innocent Palestinians who are then avenged, the dead on both sides are replaced, and so forth. And that Israel, a country dragged into war a day after it came into being and essentially at war ever since, against people that want to drive them into the ocean, does desperately need to defend itself. But where lies the crucial distinction between defense and revenge?

Over the top of its human story Munich is essentially depicting the birth of a tactic against global terrorism – swift, forceful, personal reprisal. And it says, 33 years have now passed, and has an eye for an eye brought us nearer to or further from ending this terrorism? A subtle special effect in the film’s final shot is necessary for accuracy of location, but it also makes a statement all its own.

Click for Full Post

Daily Dose of Pretty

Whitney Portal, outside Lone Pine, California

Image Copyright 2004 by Nicholas Thurkettle. All rights reserved.

Click for Full Post

From the Archive - MOVIE REVIEW - The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Originally posted 12/21/05

Full review behind the jump

The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

Director: Andrew Adamson

Writers: Ann Peacock and Andrew Adamson and Christopher Markus & Stephen McFeely

Producers: Mark Johnson, Philip Steuer

Stars: Georgie Henley, Skandar Keynes, William Moseley, Anna Popplewell, Tilda Swinton, James McAvoy, Jim Broadbent, and featuring the vocal talents of Liam Neeson, Ray Winstone, Dawn French, Michael Madsen, Rupert Everett